As regular readers and students know, I’m quite fond of having students do work. Then I am quite fond of bragging about this work, as my students are really wonderful. I have an occasion for so doing today! Over the past few weeks, we have been working on fare elasticities in my transit class, and we have a natural experiment to work with: LA Metro raised its fares last September, by a lot. The base fare increase wasn’t a big deal: It was $1.50 and it went up to $1.75, but transfer policy changed:

Beginning Monday, September 15 that will include for the first time a two-hour period of free transfers on Metro’s bus and rail system when using a stored value TAP (Transit Access Pass) card to pay for the base fare. The fare changes, following extensive public hearings and Board approval last May, will raise the price of the base cash fare from $1.50 to $1.75, the Day Pass from $5 to $7, the weekly pass from $20 to $25 and the monthly pass from $75 to $100.

I got into some disagreement with certain transit experts about this, who thought it was unequivocally good policy because of the two hour free transfer. Now, that is good policy, they are right. Unfortunately, metro changed multiple things at once, and one of my worries was that the prior transfer policy actually encouraged people to buy day passes: you had a trip that required a transfer, and the to- and from- trips would cost you $6, and with that kind of charge, you might as well buy a day pass, and with that day pass, you might undertake more trips than if you were paying by trip.

My husband, Andy, routinely did that. We’d buy a day pass for him when we set out on transit as that way, he could go that day wherever I went with my monthly pass. At $5, you could do that. At $7, you think twice about doing that, and your probably don’t do it.

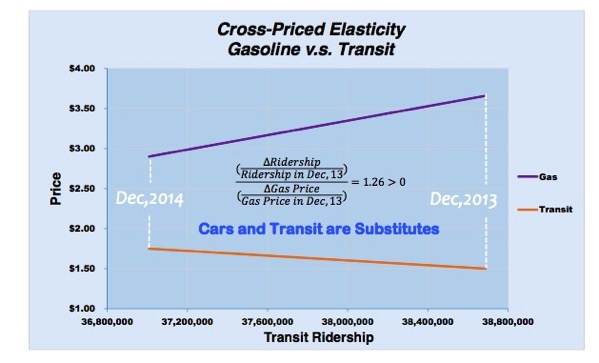

Anyway, the early evidence is that Metro succeeded in raising more revenues with the move: they had 7.7 percent bump in revenue, which is nice, but is not going to make much of a dent in their operating deficits. The bad news is that ridership also went down. Theory would tell us that this result is likely.

Brilliant student Justin Pascone lays it all out four us:

In comparing the Q2 of 2014 and 2013:

• Overall ridership is down 4.4% (from ~121M to 116M)

• Bus ridership is down 4.9% (from ~92M to 88M)

• Rail ridership is down 2.7% (from ~29m to 28M)

In comparing the change in Q2 ridership numbers and base fare

• Overall fare elasticity is -0.27

• Bus fare elasticity is -0.30

• Rail fare elasticity is -0.16

Now, APTA puts fare elasticity at about -.40, so we here in LA County are somewhat less price sensitive than on average, but I think this is an effect of who rides: we are probably serving a lot of transit dependents who really have little choice but to eat the fare increase. One thing to note: the rail riders are much less likely to step off than the bus riders. Now, there are multiple possible explanations: rail riders are getting such a good ride that they don’t mind paying more for it. But it is also likely that your rail passengers are somewhat higher income and, thus, less price sensitive. It could be both.

One possible answer to the budgetary and justice woes with transit fares might be , for example, to price discriminate and charge your rail riders more.

Justin Bleeker took an extra step to help us understand that these aggregate modal elasticities hide quite a bit of variance, however, and soaking our rail riders would have pretty steep distributional effects as well:

I suspect that if we broke that bus figure out by a sample of bus lines, we’d have a similar situation, but it’s pretty clear: riders along the Blue Line, in south Los Angeles, are pretty price sensitive, and higher fares meant less travel.

This is not good news.

Also in the not-good-news department: the confounding thing is that metro ridership was declining even before the fare increase. (WHY IS THIS HAPPENING?? ARE WE NOT SPENDING BILLIONS ON TRAINS FOR YOU PEOPLE???).

I’ll revisit these questions later in the week with more cool student work.